The Milk of Dreams | The Look of Science

I’ve not had much time or mental energy to blog this year - with a new job and my book finally on the way - but I’ve been feeding my interest (particularly in art and science) through exhibition visits when I can. I was lucky to carve out some time to visit the Biennale in Venice, after a Covid gap, as so many of the ideas and themes spoke to areas that interest me in interactions between art and science: the definition of the human (body), the relationship between human and nature, and our responsibilities to the planet.

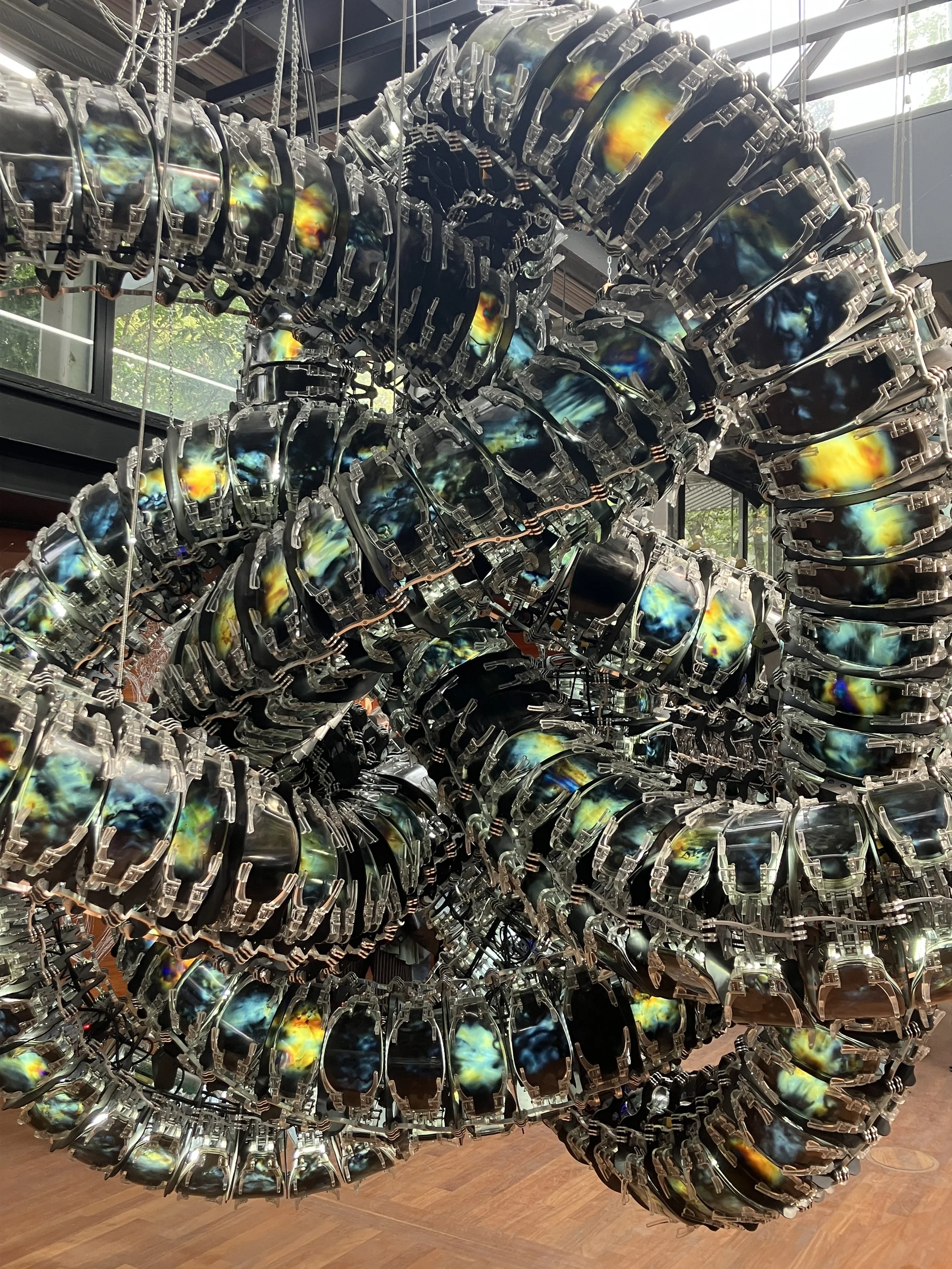

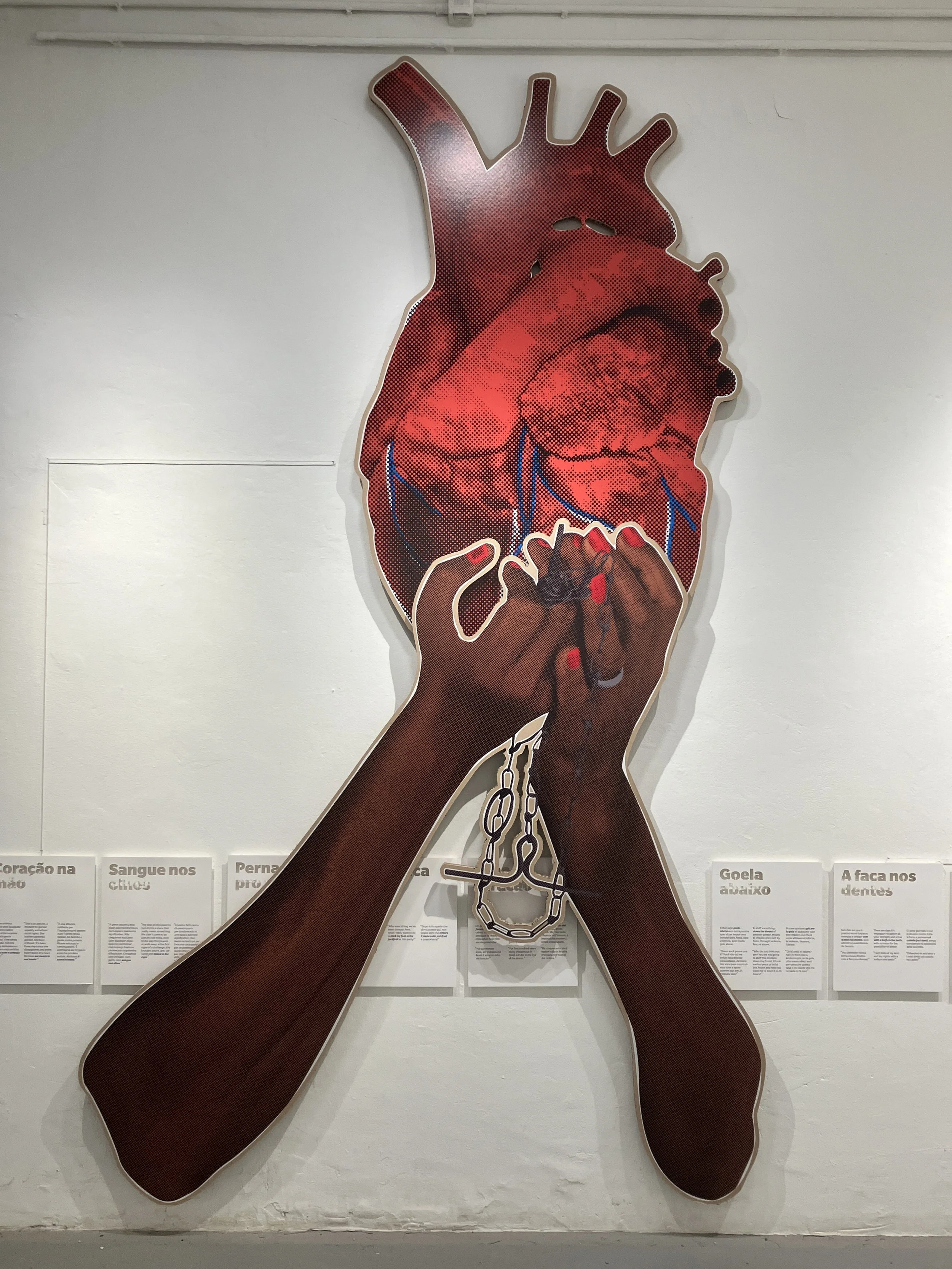

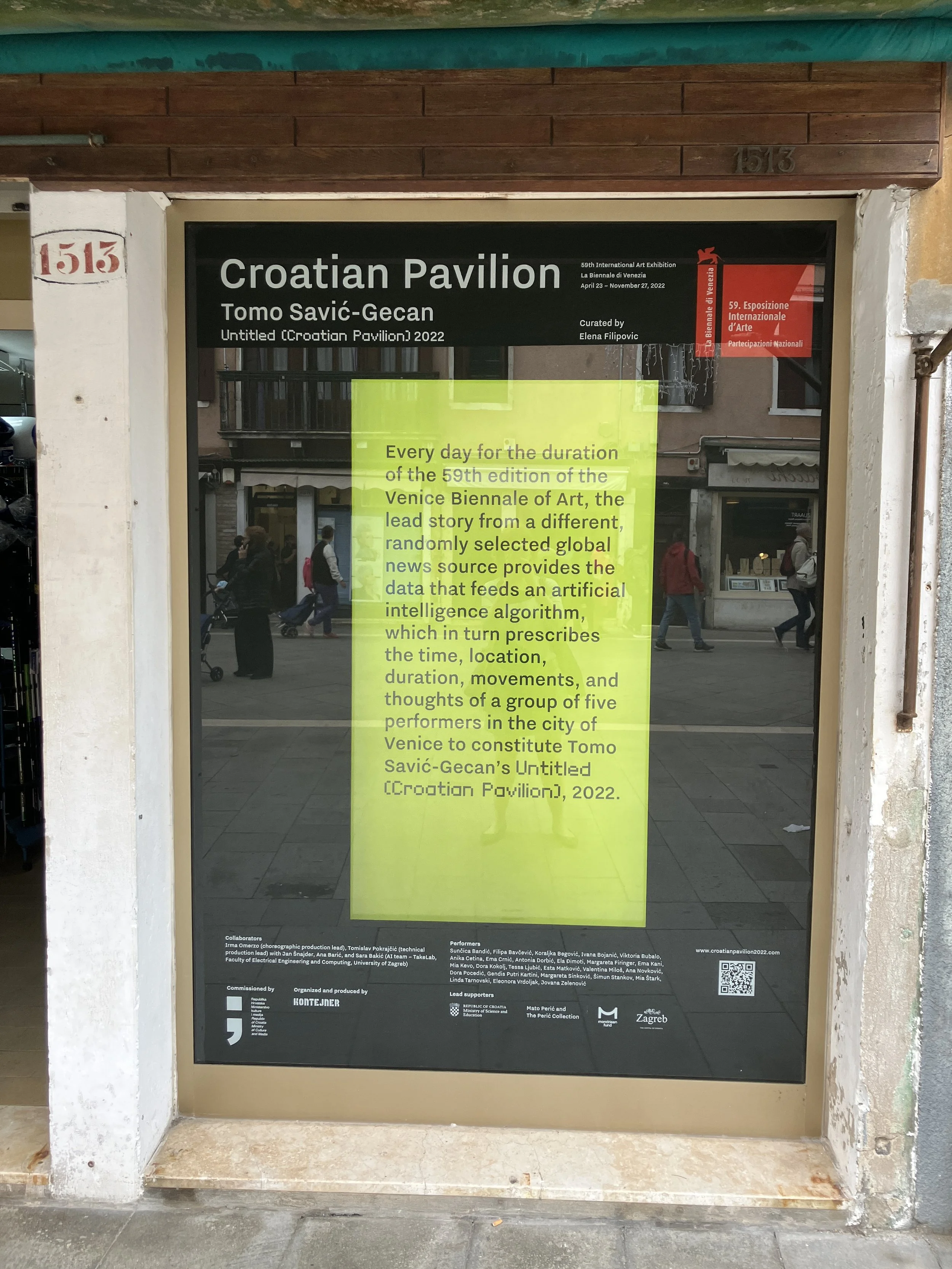

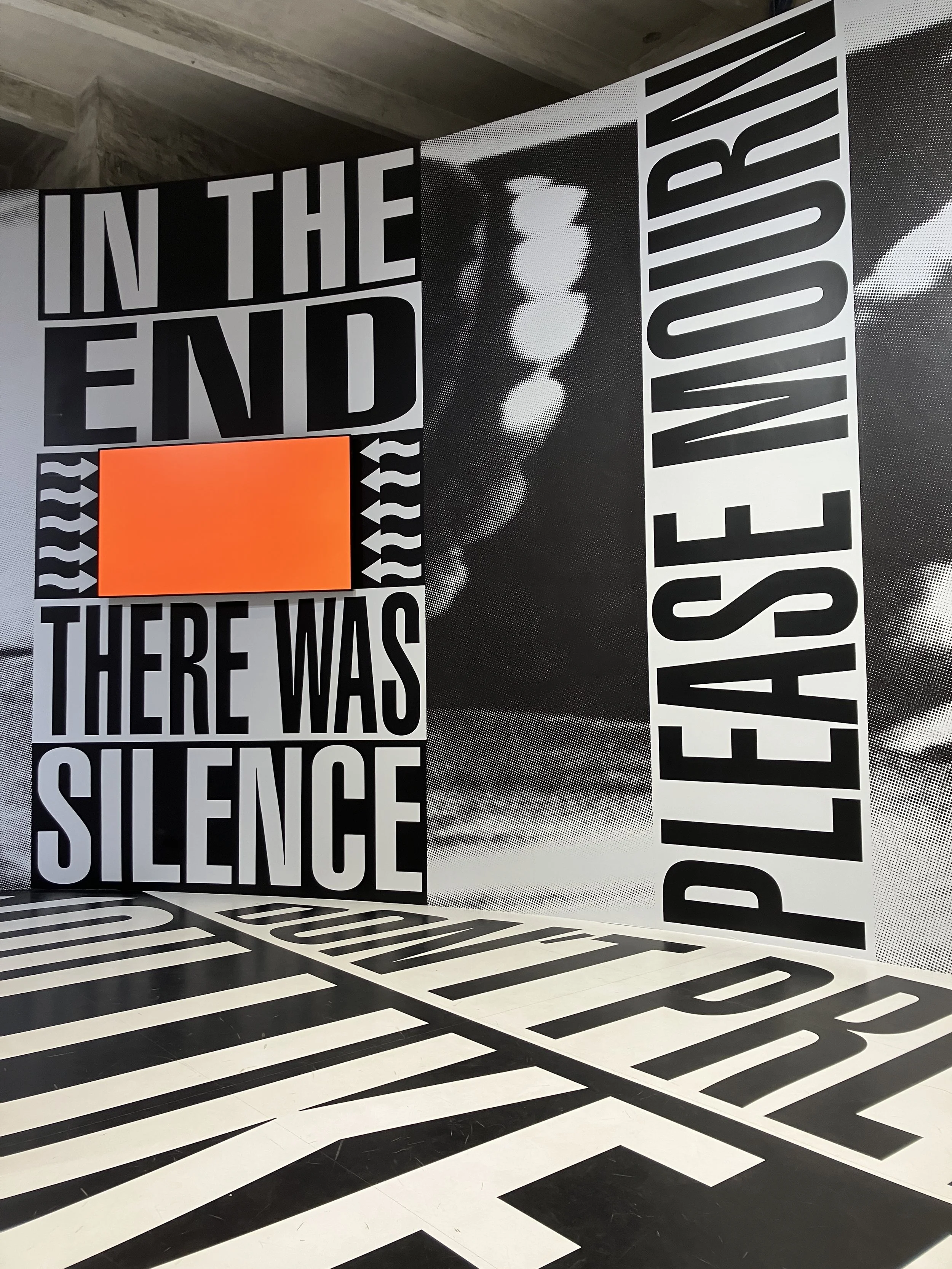

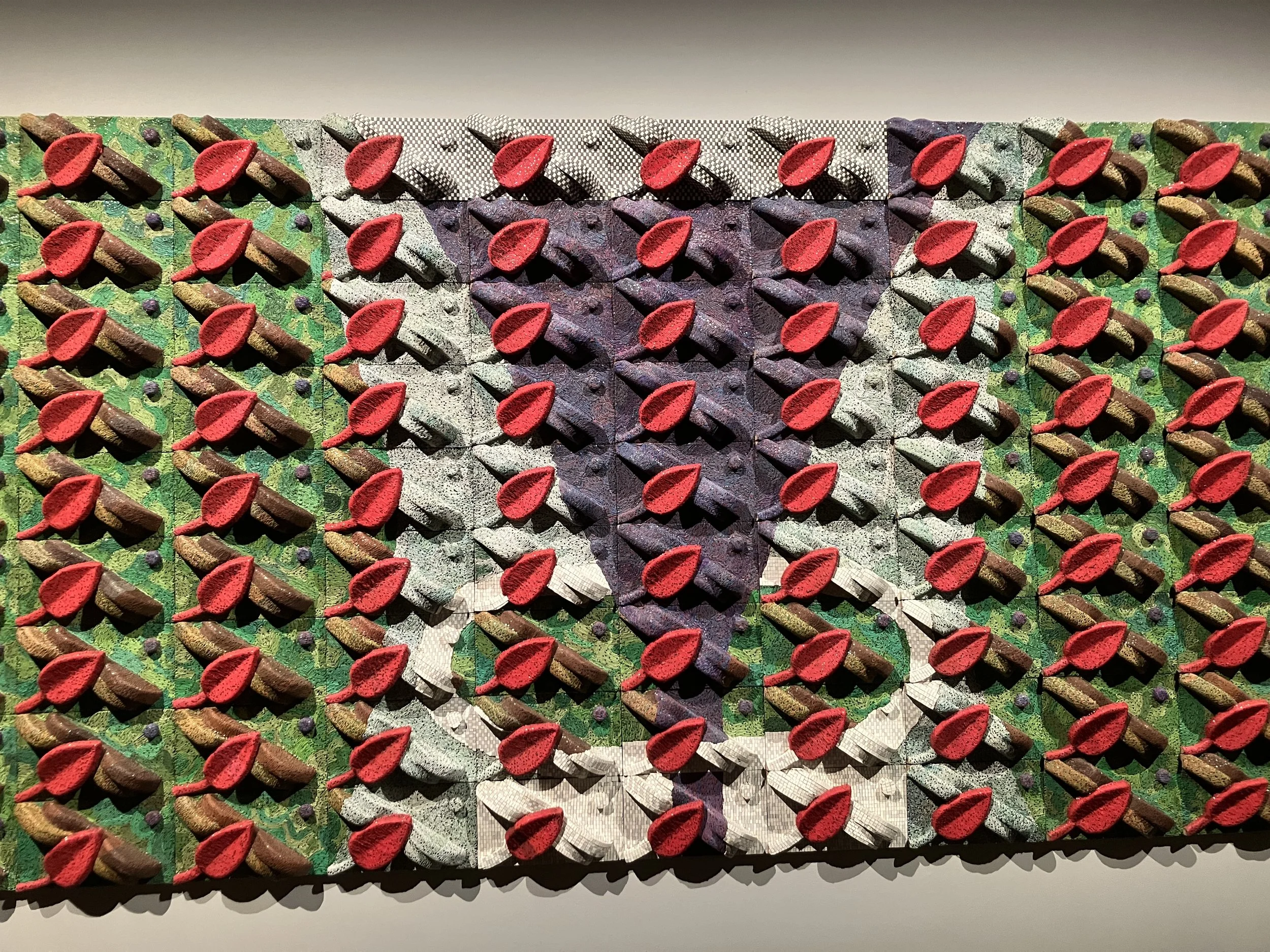

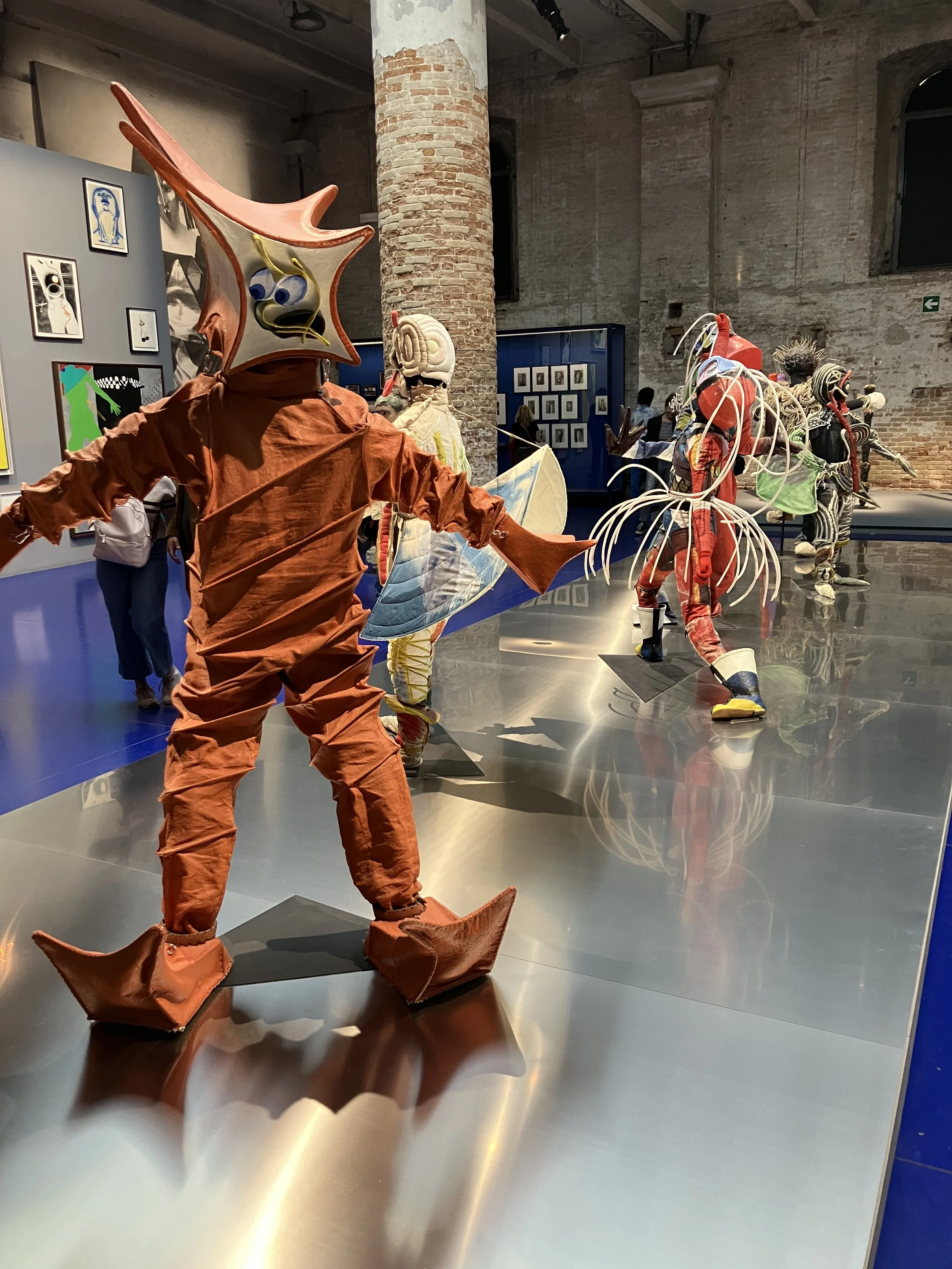

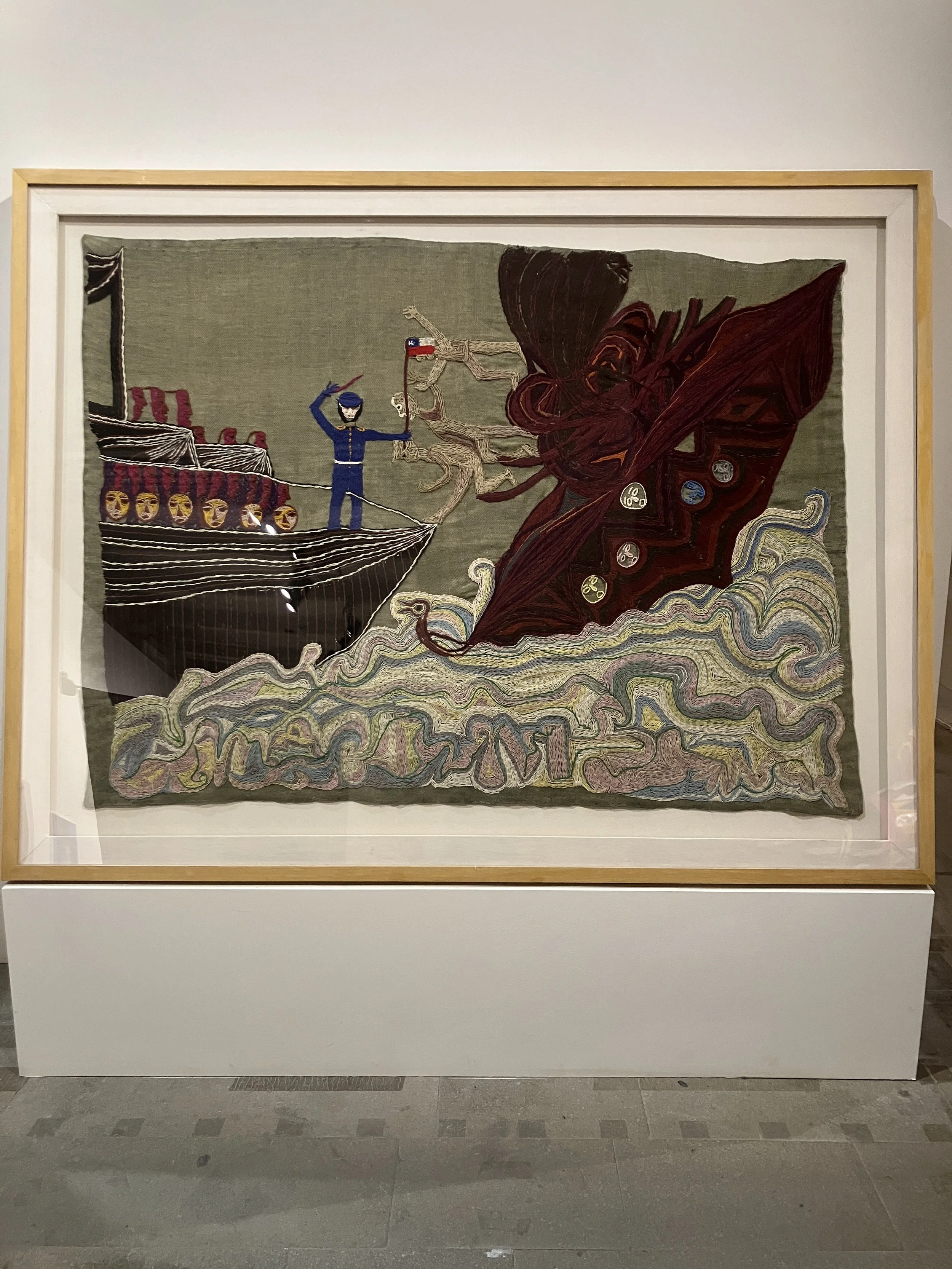

Below a selection of photos (largely also on Instagram) give a visual tour of my wanderings through the different pavilions, exhibitions and collateral events. As a whole, the biennale allowed me to discover a feast of new artists, and I was particularly pleased to see so many female and indigenous artists given prominence. I thought the exhibitions in the Giardini and Arsenale were notably well curated this year, with a real sense of pace, changing media, size and complexity, and the rare ability to leave you invigorated at the end. I was also captivated by a number of national pavilions: Francis Alÿs’s films of children’s games across the world for Belgium; Zineb Sedira’s rich film and stage sets for France; Yuki Kihara for New Zealand unpicking Samoan ideas of Fa‘afafine (third gender); and Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s monumental tapestries of Roma history and culture for Poland.

I was also struck by the four sections showing interventions of loaned works by historic female artists among the contemporary exhibits, which I felt worked especially well, drawing out the older narratives behind the modern works and, for me, particularly showing a long interest by women artists in the ideas and objects of science. ‘The Witch’s Cradle’ looked at the disintegration of clear divisions between body and technology, human and nature, male and female in surrealist art; ‘Corps Orbite’ considered female artist’s important role in textual art; ‘Technologies of Enchantment’ showed the crucial adoption of computer technologies in avant-garde art; ‘A leaf, a gourd, a shell …’ looked at how women artists and scientists studied and learnt from the role of vessels in nature; and ‘Seduction of the Cyborg’ highlighted the female body as a particular site for considering body and machine.

Two national pavilions especially gave me real pause. Lara Fluxà for Catalanonia in Venice and Gian Maria Tosatti for Italy. Fluxà’s presentation Llim (silt) filled the space with a vast chemical apparatus - both visually compelling and quietly mesmerising - to materialise Venice’s foundations in water and its prowess in working with glass, riffing of the root of the word alchemy in the Arabic word for the black mud of the Nile. Tosatti’s two-part ‘History of Night’ and ‘Destiny of Comets’ created an immersive visual tour through the vast (decaying) Italian industrial complex, before imagining a dystopian release into a different future for its thwarted working class. Both presentations drew heavily on ideas of the aesthetics of science - chemical apparatus, functional glassware, rubber tubing, heavy industry, painted instructions, embossed metal platforms, concrete pillars, blinking lights.

Both reminded me of some initial thoughts that I had in 2019 on visiting Mike Nelson’s installation The Asset Strippers at Tate Britain, where I thought about how scientific objects can become artworks in a gallery space. Together these have left me thinking again about the aesthetics of science - how visually we have been trained (by both artists and scientists) to expect science, and its different forms, to look over different historical periods - and how artists therefore think about working with science today, and vice versa. I’ve got the kernel of a research/book idea on ‘The Look of Science’ germinating, which I’m hoping to have time to tend in the coming year. Ideas and comments welcome!