On Vilnius: What constitutes a historical object?

Continuing our tour of Eastern European capitals, we spent some time in Vilnius over Easter, capital of Lithuania. As readers of this blog will know, I’ve been equally fascinated and perplexed by the varied approaches to history that museums have shown in Eastern capitals that I’ve visited before. This time I return similarly so, but for different reasons.

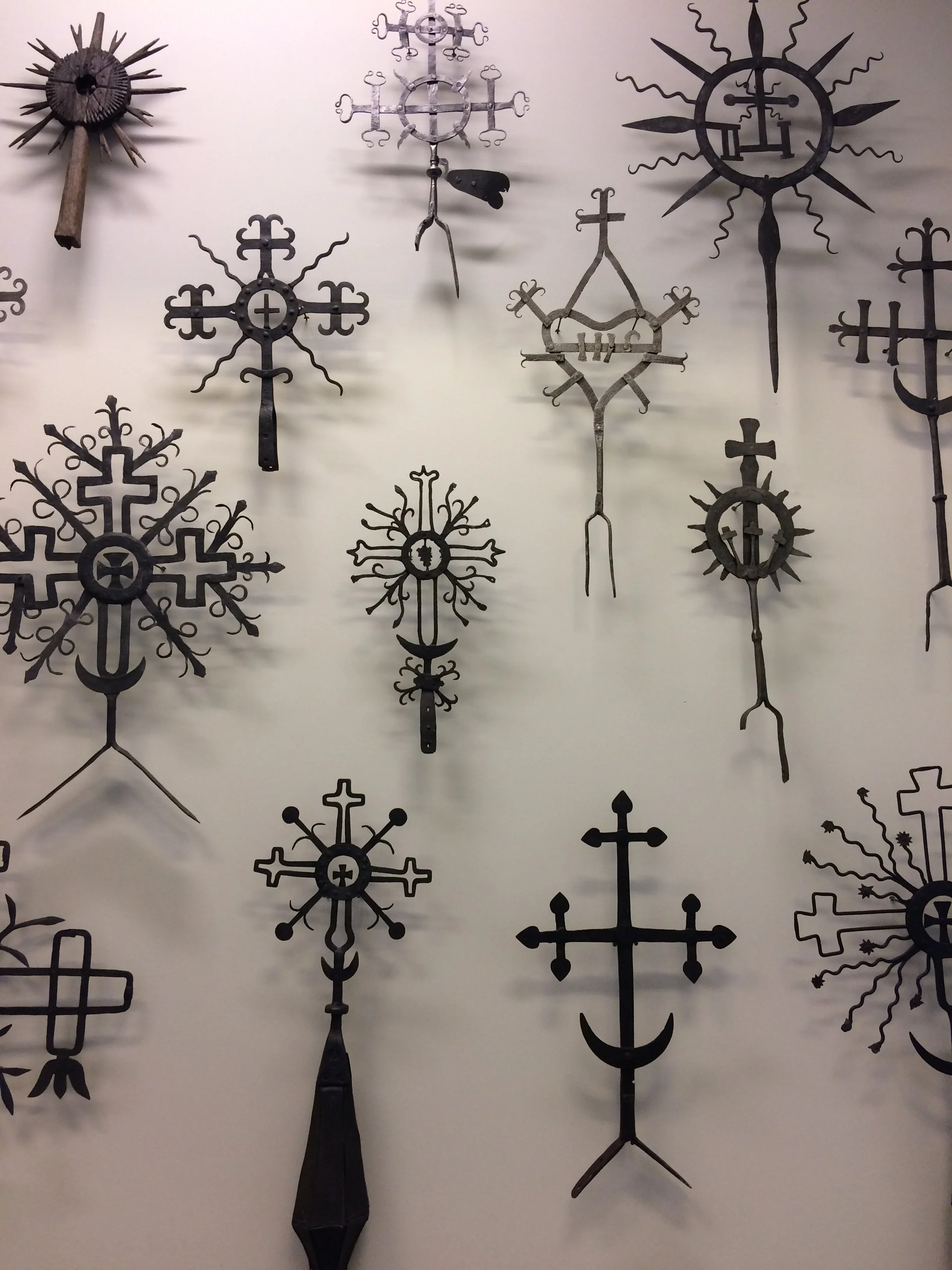

Vilnius is a city of spectacular churches with extraordinary interiors. I was particularly intrigued by the chapel in the Gates of Dawn, where metal votive offerings of body parts, brought by centuries of pilgrims, are nailed up all around the icon of the Virgin Mary. The gate is the only remaining one of ten that once formed part of the city’s defensive fortifications as the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The city’s history is chequered with warfare and invasion but also a strong sense of Lithuanian identity.

This is what is most striking in its national monuments. Lithuania’s only king, Mindaugas, sits enthroned as a statue outside the National Museum. Just around the corner towers the powerful statue of Gediminas and his horse, credited with being the founder of the Lithuanian grand duchy as well as of Vilnius as a city. Both of these men gained their importance during the period of national rebirth in the 19thCentury. Both of their statues have been installed since 1996.

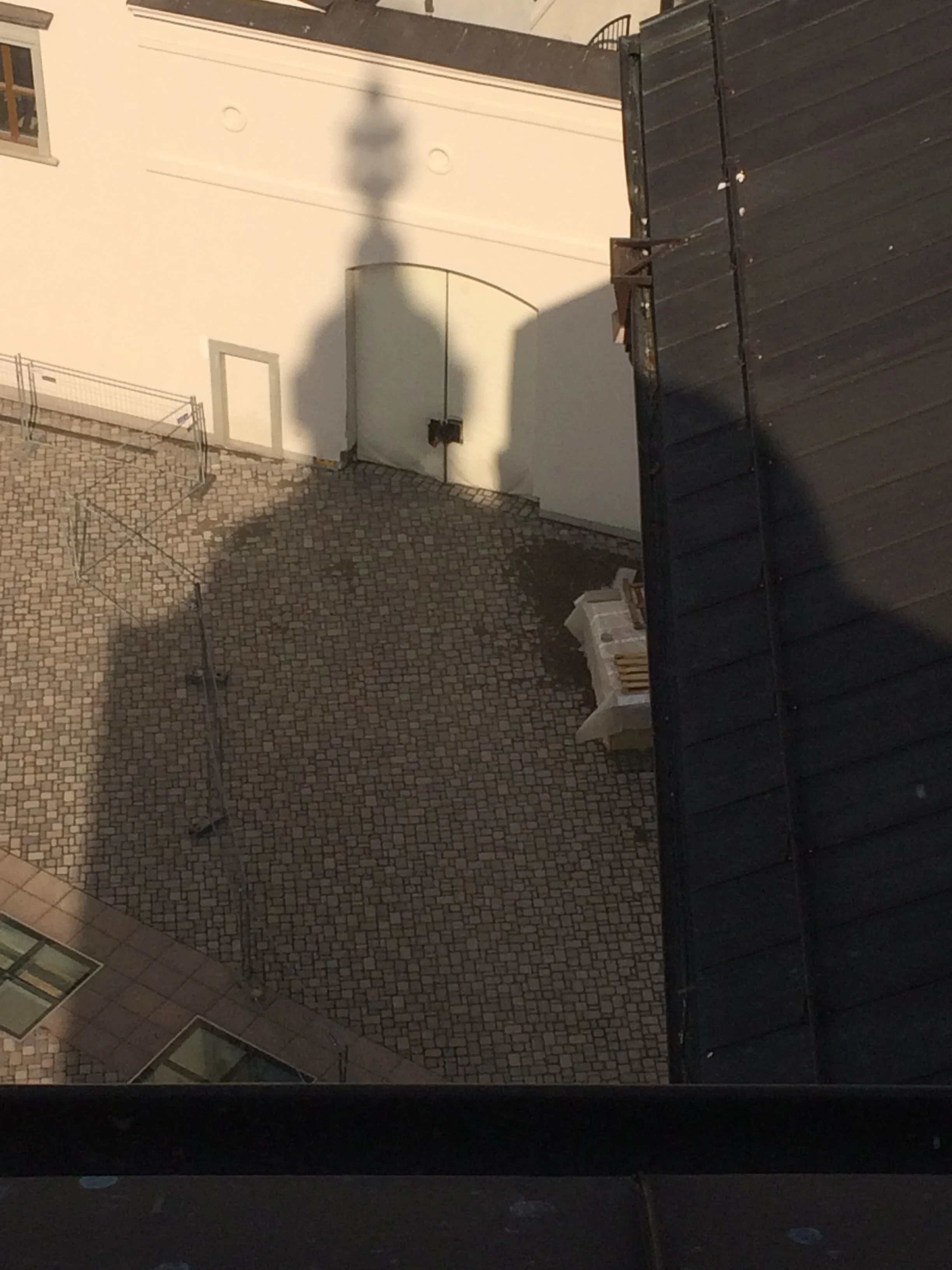

Both statues are also situated in relationship to the set of buildings which form the historic heart of modern Vilnius: the Cathedral, Grand Ducal Palace and Gediminas Tower. The hill that must be climbed to reach the tower is currently closed for repair work, but we duly looked around the cathedral and palace with great interest. It must be said that the palace is an extreme example of the ‘book on a wall’ brand of exhibition text, but we learnt a huge amount about the early history of Lithuania, until we gave up because there was just so much to read. The set-piece rooms in the palace are clearly modern reconstructions based on archaeological finds shown in the basement, and filled with a range of furniture from other collections, or copied paintings, but you get a clear sense of the rich and complex medieval and renaissance history of the region.

What isn’t explained anywhere in the exhibits, and was entirely unclear to us until we looked online, is that the entire ducal palace building was only started in 2002, and open to the public since 2013. The original was almost entirely demolished in 1801 on the orders of Tsarist Russia. The current palace is only partly based on archaeological evidence and images, and has replaced a genuine historical house constructed out of the ruins that was itself over 200 years old.

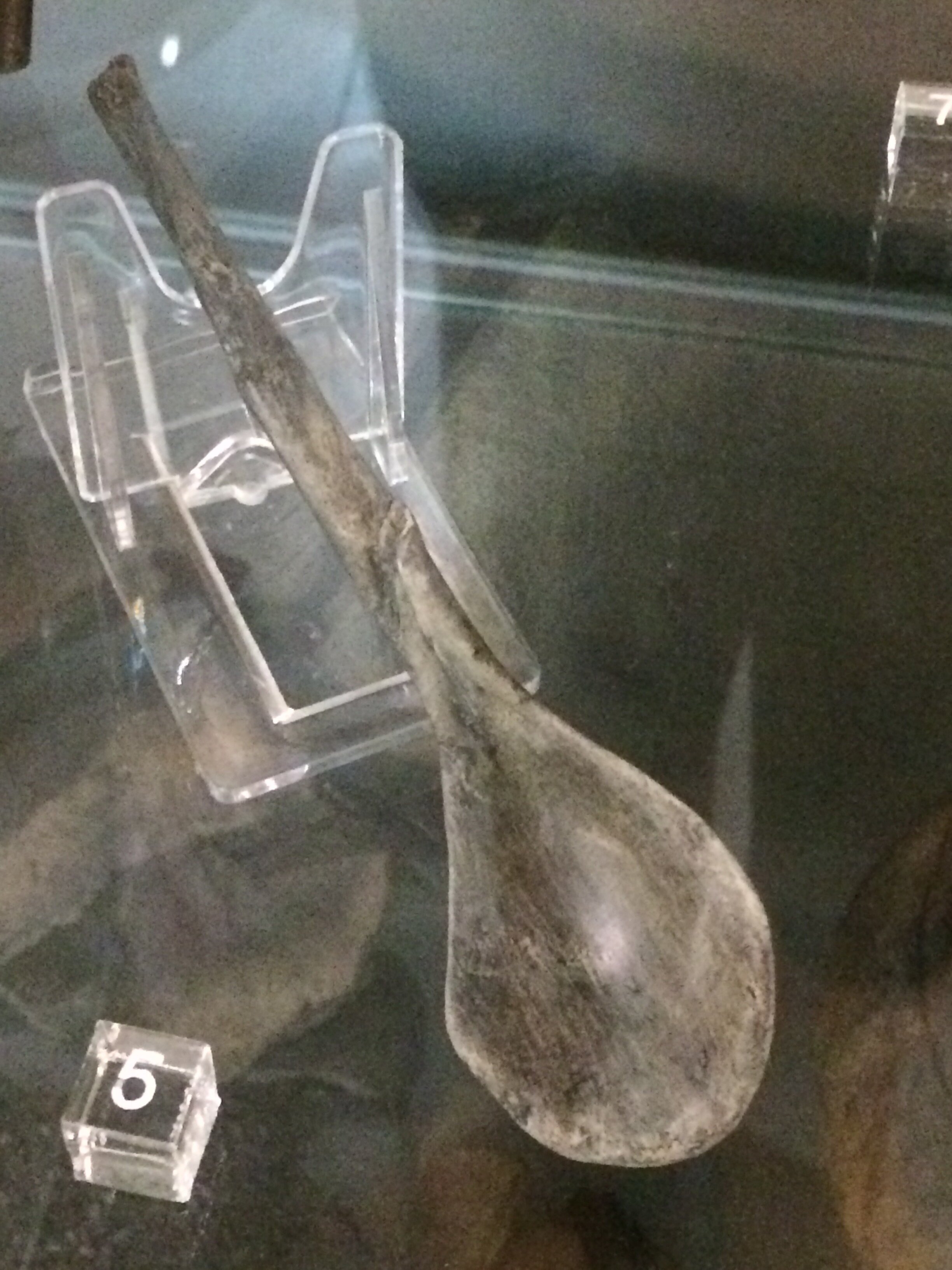

I’ll admit to some outrage at this until a later guided tour of the Cathedral crypts gave me pause. The guide talked to us about how the cathedral had stood there since 1251 when Mindaugas started construction after his conversion to Christianity. However, the building itself has been destroyed, rebuilt and restructured a number of times. Yet the way she described this as different incarnations of the same building made me think about the old philosophical puzzle about whether a spoon remains the same object if the handle and then bowl have been changed. For Lithuania, removed from the map of Europe for almost 200 years by first Tsarist Russia and then the USSR, it doesn’t matter that the palace is not the original building, it is the next incarnation of this central object of national identity for modern Lithuania. It is still the same spoon.

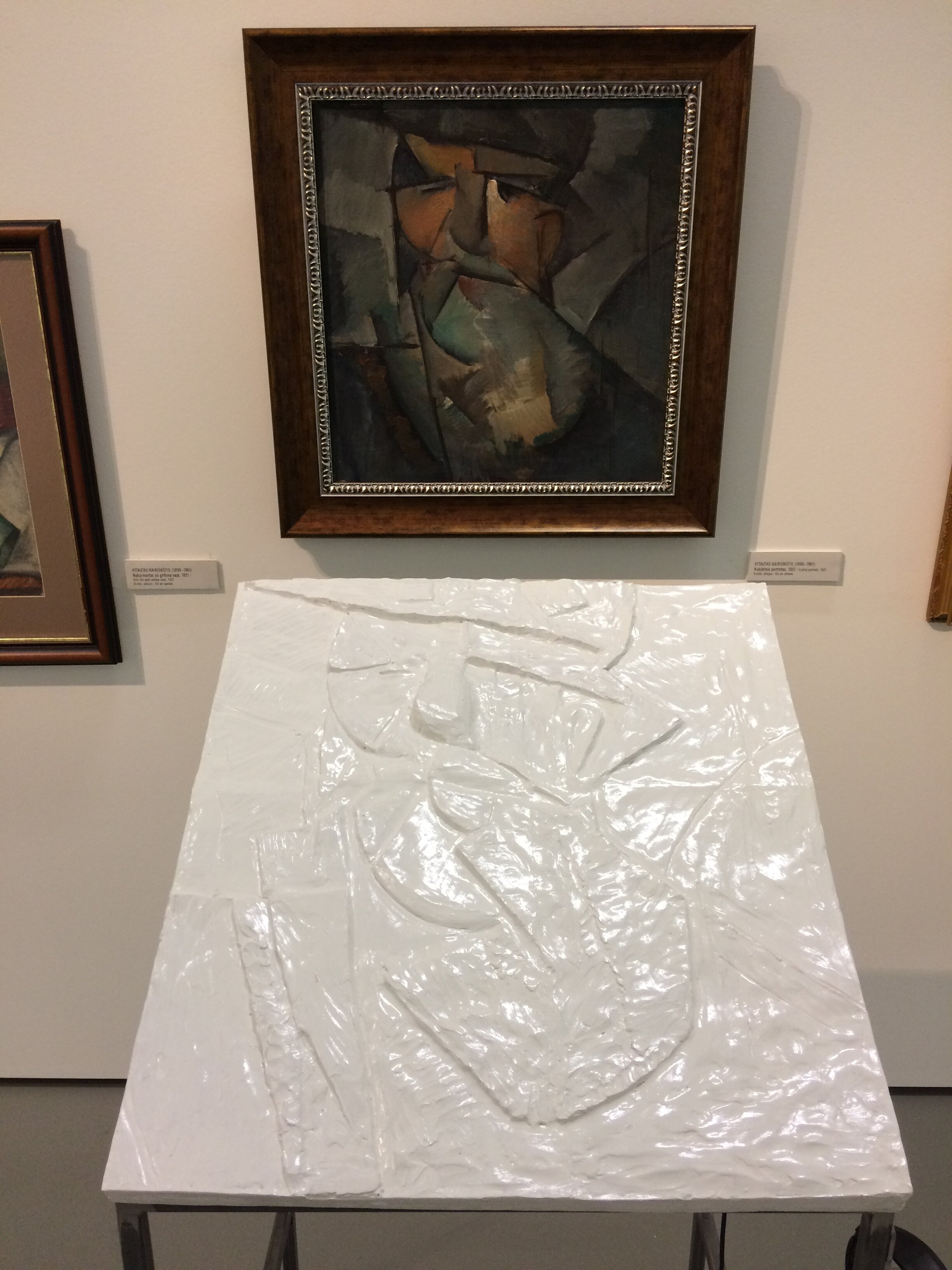

The National Museum was almost the last place that we visited and really impressed me. A small series of beautifully curated rooms combined the national collections of antiquities and ethnography to talk about the history of the museum itself as an expression of national identity, and of objects as a means to cohere a sense of nationhood. It focused particularly on the birth of all of these collections and institutions in the period of national awakening in the 19thcentury when both Mindaugas and Gediminas gained their importance, subsequent to Russia’s demolition of the ruins of the original palace. Perhaps the lesson here is always to visit a museum first?!