On Stuttgart: Collecting and Kirches

Stuttgart reminded me quite distinctly of Croydon (where I live). With much of the city centre destroyed in the Second World War, Stuttgart is now a concrete paradise, distinguished by multi-lane roads and nondescript high-rise buildings. A bit like Croydon, its trajectory also has a similar arc, initially the seat of the kings of Württemberg, or in Croydon’s case home to the archbishop of Canterbury, Stuttgart is now the state capital, an important economic and industrial centre in the 20th century, and now finding its place in the 21st.

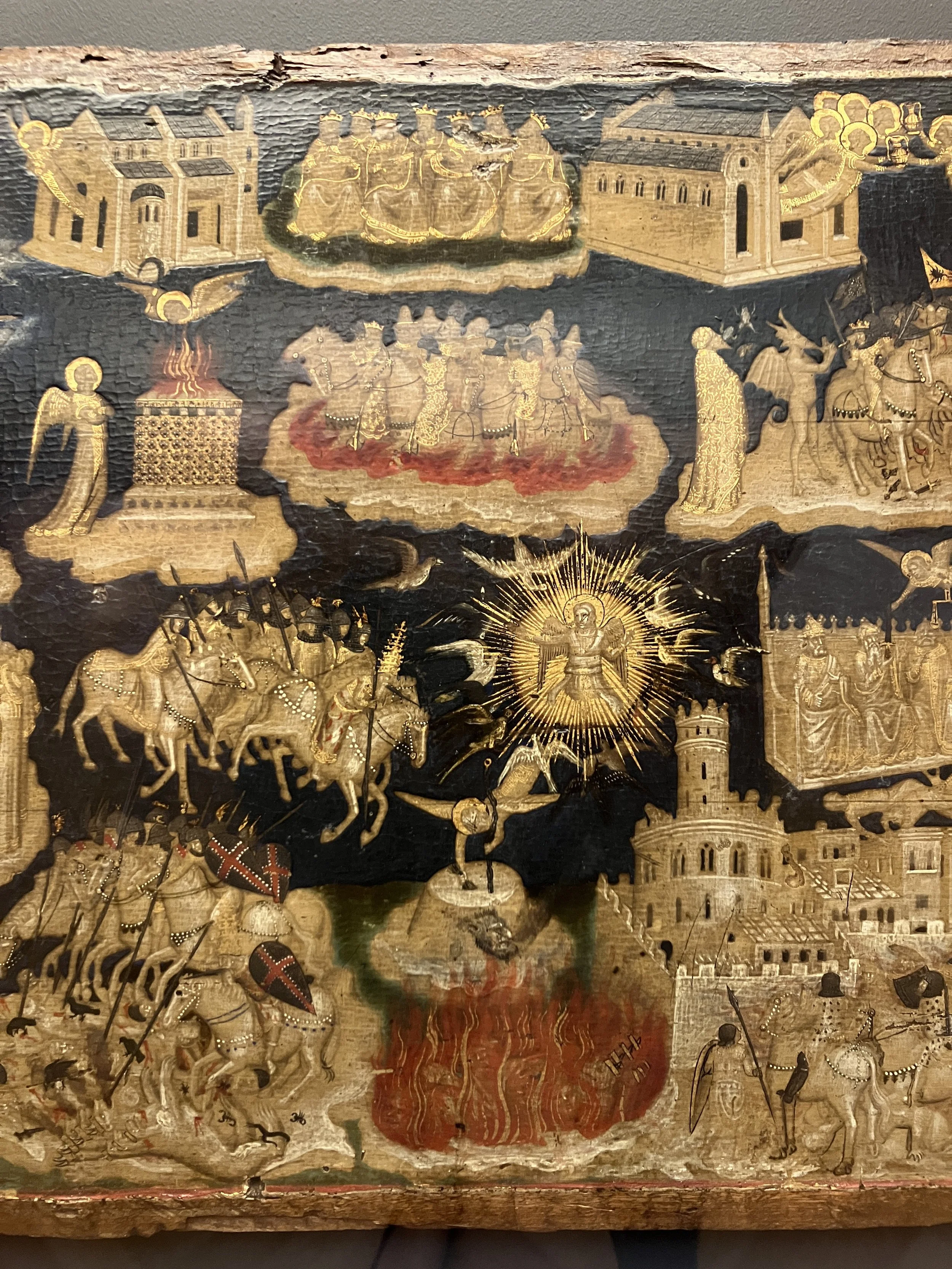

Unlike Croydon, Stuttgart has two significant art museums, from which I learnt this history, and by which I was impressed on my recent visit. The Staatsgalerie was founded by King Wilhelm I as the ‘Museum der Bildenden Künste’ in the 1830s. It has a striking post-modern extension by James Stirling opened in 1984, and clearly an active friends organisation which has contributed significantly to its impressive holdings. These tell the story of art - local, national and international - from the 15th century to the present day. I learnt about the importance of Ulm as an artistic centre in late-medieval and early-modern Swabia, right through to the role of Willi Baumeister as a local contributor to modern abstraction. I saw how 18th-century German portrait and landscape art spoke to similar enlightenment ideals to what I know in Britain, and particularly enjoyed presentations of Edward Burne-Jones ‘Perseus Cycle’ and Oskar Schlemmer’s ‘Das Triadische Ballett’. The temporary exhibition ‘This is Tomorrow’ showed the institution’s commitment to staying relevant to its audience, diversifying the artists and subject-matter given importance in the collection.

The Kunstmuseum is housed in a striking glass box on Stuttgart’s central Schlossplatz. Its roots are in the city art collection, previously called the municipal, and latterly city, gallery. The collection was also founded in local artists, initially focused on Swabian Impressionism and opened to the public with the intention of demonstrating the city’s cultural significance. Later directors focused on local artists’ role in modern and contemporary movements. There is a significant holding of works by Otto Dix (whose ‘Self Portrait with Jan’ particularly struck me) and it was here that I first encountered Willie Baumeister’s beguiling abstract paintings. Later key artists include Dieter Roth and Wolfgang Laib. The museum displays the latter’s beeswax room, which is a surprising and extraordinary sensory experience. The special exhibition on Otto Herbert Hajek, again introduced me to a new artist, and particularly engaged with how his large outdoor sculptures shaped Stuttgart’s cityscape, including the Sclossplatz immediately outside.

The Schlossplatz perhaps speaks to Stuttgart’s modern cultural status. It is a mix of reconstructed and repurposed 19th-century buildings, combined with contemporary arts spaces - the Staatstheater is here as well as the art museums - and the bustle of commercial dining and retail. Just behind it I happened to look into the Stiftskirche, and what a discovery! The 14th-century gothic church was largely destroyed in the Second World War but has been rather wonderfully restored, combining a new modern interior with surviving tombs and sculpture. I loved the bold contemporary ceiling, gesturing to the original nave roof, and the modern stained glass mixed with older sculptural groups and tombs mounted on metal struts.

I felt the kirche radiated a quiet confidence in its past, present and future, something also embedded in the collections and curating of the city’s impressive art museums.

Photos from the Staatsgalerie

Photos from the Kunstmuseum

Photos from the Stiftskirche