May you live in interesting times: Some thoughts on the Venice Biennale 2019

I think October must be the perfect time to visit Venice. The light is low and warm, the crowds have thinned out a little, and the rain clouds largely stay away. It may seem late to visit the Biennale (which opens in May) but it was excellent timing for me to explore a feast of ideas and artworks after a busy year. I was lucky to spend almost three whole days solely visiting the exhibition, national pavilions and collateral events. Although I didn’t get to everything, I saw hundreds of things to provoke and inspire.

The theme of this year’s biennale ‘May you live in interesting times’ has been discussed by the President, Paolo Baratta, and curator, Ralph Rugoff, as evoking both times of challenge, even menace, and also simply times understood in their full complexity. Perhaps art can be a kind of guide for how to live and think in such ‘interesting times’? Many of the artists have responded directly to this provocation, evoking and commenting on some of the key challenges and opportunities that interest us today.

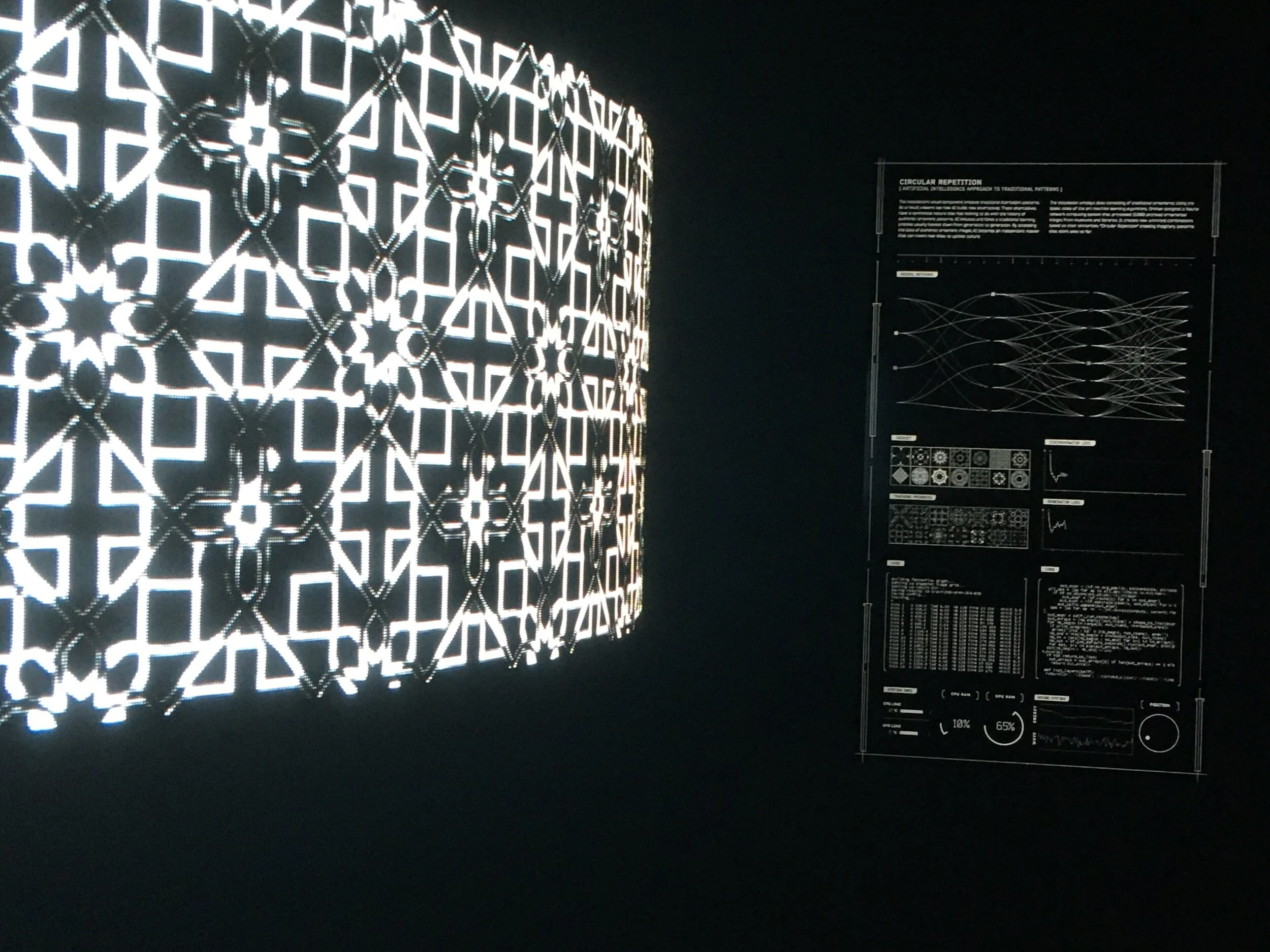

I was immediately struck by how present digital art and technology are throughout the displays. Not only do a significant number of artists work in film – which makes an interesting intervention in the pace at which you move around the pavilions and exhibition rooms, causing you to pause and absorb – but the technology used to create and display their works, I thought, was interestingly present. In ‘3x3x6’, a collateral event staged in Venice’s old prison, Shu Lea Cheang questioned modern technologies of surveillance and incarceration, through the stories of ten people incarcerated because of gender or sexual dissent. The projector stack stands right at the centre of the main interactive room, with main frame displayed as a visual treat in its own right next door. At the centre of the German pavilion, a vast scaffold supports Natascha Süder Happelmann’s installation ‘Tribute to Whistle’ to fill the space with a collaborative sound installation. The film piece that particularly inspired me was Ryoji Ikeda’s ‘data-verse 1’ combining large data sets from CERN, NASA, the Human Genome Project etc showing beautifully how data constructs our visual understanding of micro and macro science.

Many artists also engaged with environmental questions and concerns around climate science. In the French pavilion, Laure Prouvost’s immersive, overwhelming installation ‘Deep see blue surrounding you’ plunged you into a surreal visual questioning of how we interact with the oceans. In the New Zealand pavilion, aptly housed in the former palazzo home of the Institute of Marine Sciences, Dane Mitchell compiles an endless inventory of vanished or invisible phenomena, extinctions, and past events, which are broadcast from trees in the garden, and at sites across Venice, while a paper list slowly fills the empty library space upstairs. For Luxembourg, Marco Godinho produced the entrancing piece ‘Written by Water’ commenting on how people and words migrate, through compiling a vast installation of hundreds of notebooks washed in different seas.

Beyond, and connected to this, many artists compellingly addressed larger questions around how we live with each other, as well as the natural world. Many pavilions foregrounded underrepresented voices, whether due to race, gender or class. For Canada, Isuma’s video art looks at forced relocation of the Inuit people and how media can help to reclaim those histories today. The provocative title ‘History Has Failed Us, but No Matter’ for the Korean pavilion, allowed three female artists to challenge narratives of the past. Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca’s glorious ‘Swinguerra’ for the Brazilian pavilion focused on popular dance as a means of expression and coming together (a timely challenge for our Netflix, talent-show era), and Angelica Mesiti’s film ‘Assembly’ for the Australian pavilion looks at the spaces and technologies of democracy in Italy and Australia.

Other artists, indeed, seemed to turn to broader questions of space and abstraction, how we live in and see our environments. I was surprised to be so absorbed by Leonor Antunes installation for the Portuguese pavilion, ‘a seam, a surface, a hinge or a knot’, which filled the palazzo with abstract forms, responding to Venetian craftsmanship and architectural design history. For sheer inventive use of space, I loved the Uruguayan pavilion, in which Yamandú Canosa created ‘La casa empática’ combining paintings, drawings, photographs and mural works into a single ‘landscape’ covering the walls. In the Arsenale exhibition, Liu Wei’s ‘Microworld’, created a vast modernist stage set, that could be both microscopic protons or macroscopic parts of aeroplanes.

The list above also shows how many artists have placed collaboration at the heart of their practice, working to give voice to different voices and lived experiences. I found this biennale a thoughtful and timely way into thinking about our ‘interesting times’, how we might bring the positives out from the negatives, and how art can help to act as a guide for how we think about the world.

You can get a sense of my ‘live’ responses, and my own way of living with others and tech while at the biennale, through my Twitter commentary here. Some photo highlights below.