Biennale with baby

The cafe in the central pavilion of the Giardini is a baby sensory paradise.

Having a baby changes everything. I knew that in principle perfectly well, but 3 months since the arrival of little Alfie, there are changes that I hadn’t expected and changes that I had. There are of course the sleep-poor nights, the nappies, the feeding, the smiles, the baby chatter, but I hadn’t anticipated how much I would enjoy taking Alfie around art displays.

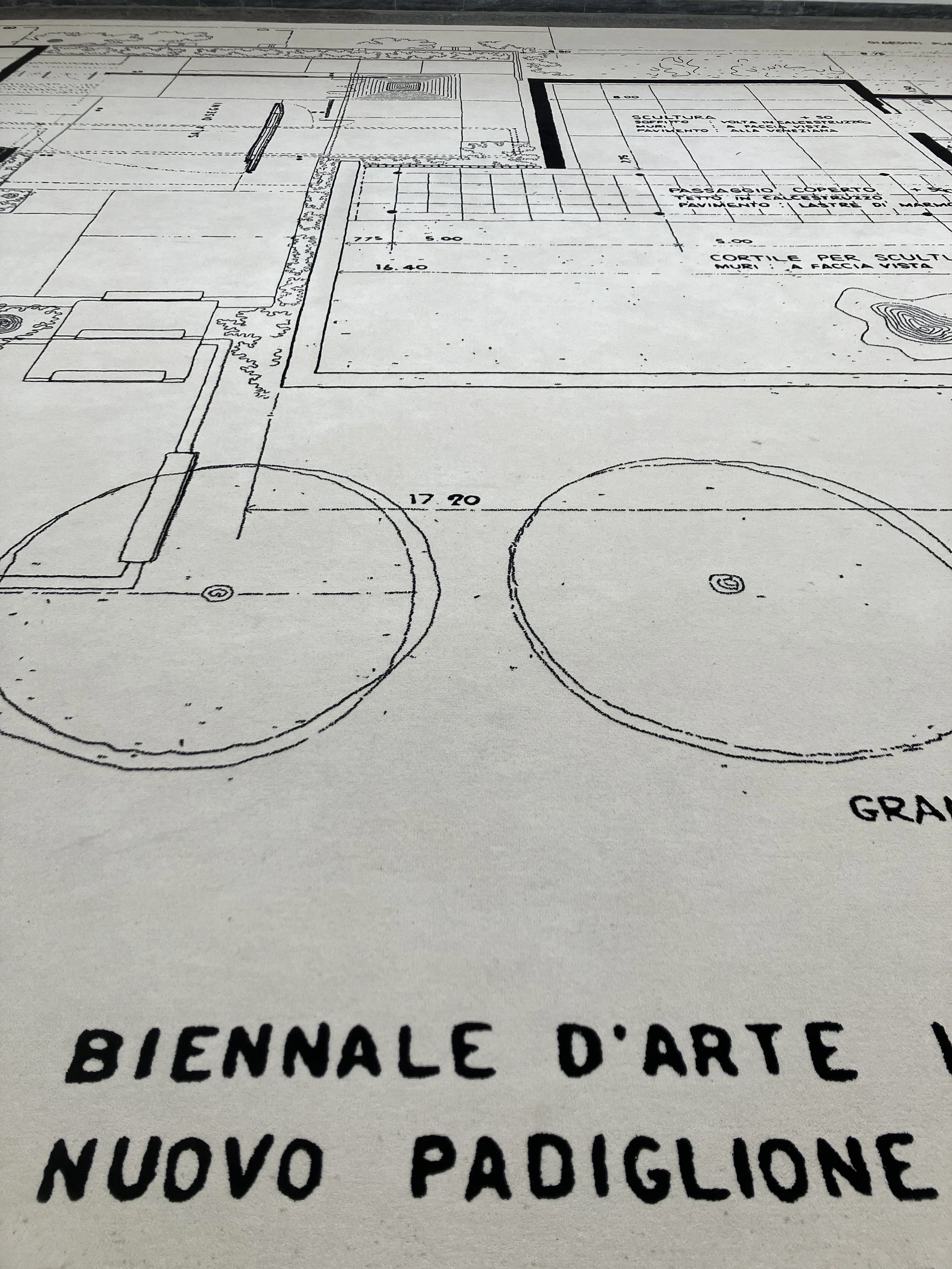

In early November, we were lucky/brave/foolhardy enough to attempt our first holiday with Alfie and flew to Venice for a few days. As readers of this blog know, it’s a city we know and love, so we thought nice and low-key to visit in this new unknown situation. Due to Covid-19 delays, this year is the architecture biennale, which I’ve never visited, and a grey heavily rainy day offered the perfect opportunity.

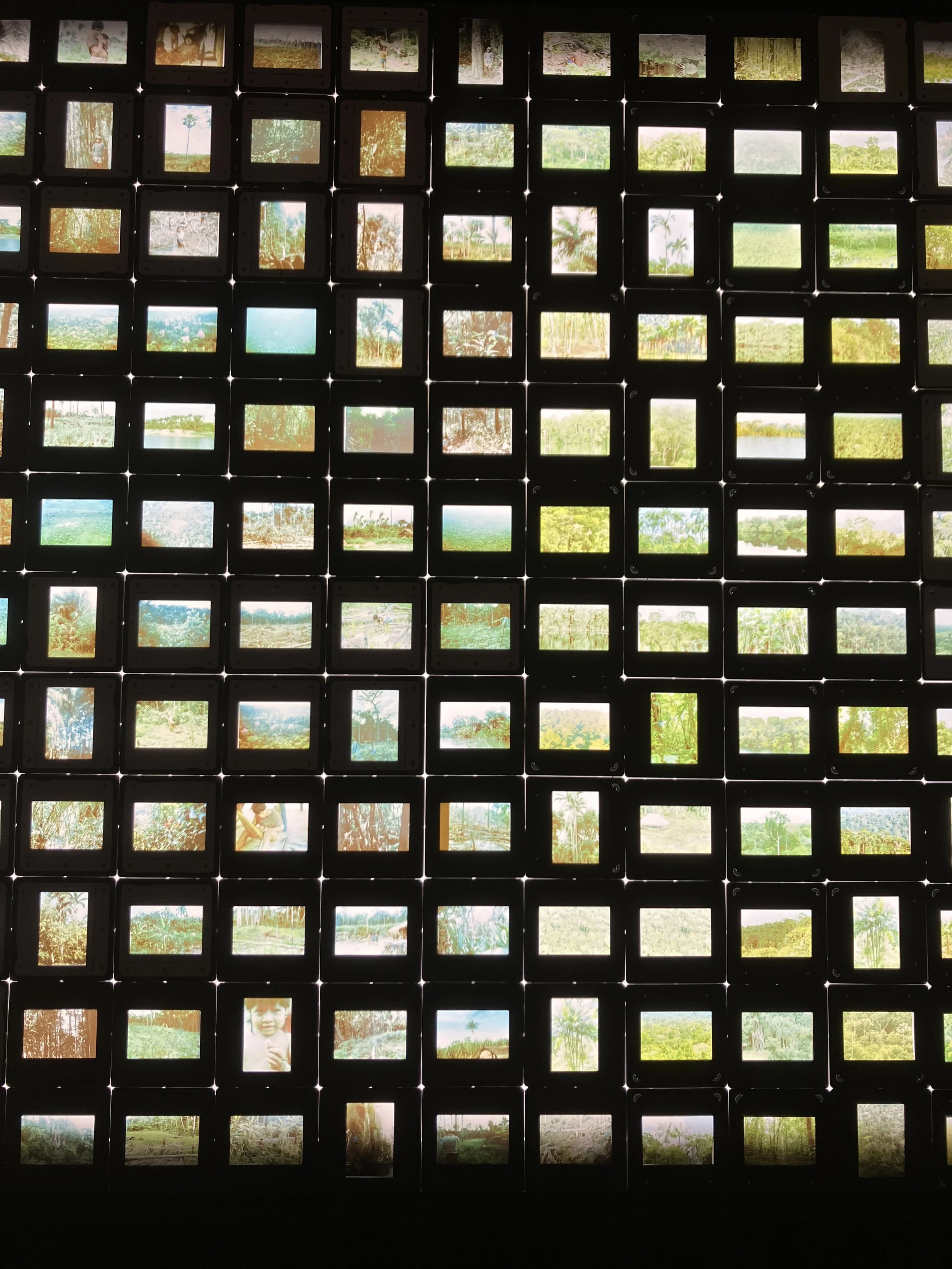

Not only do the biennale sites offer the only decent baby changing that I found anywhere in Venice, as well as good step-free access for a pushchair and nice wide spaces for wheeling one around, but the sensory nature of the biennale was perfect for a small, developing baby. I was, perhaps naively, surprised by how similar the architecture biennale felt, in many ways, to the art one. Lots of large-scale installations, collaborative projects, focus on indigenous knowledge, protest, climate change and the relationship between space, land and identity.

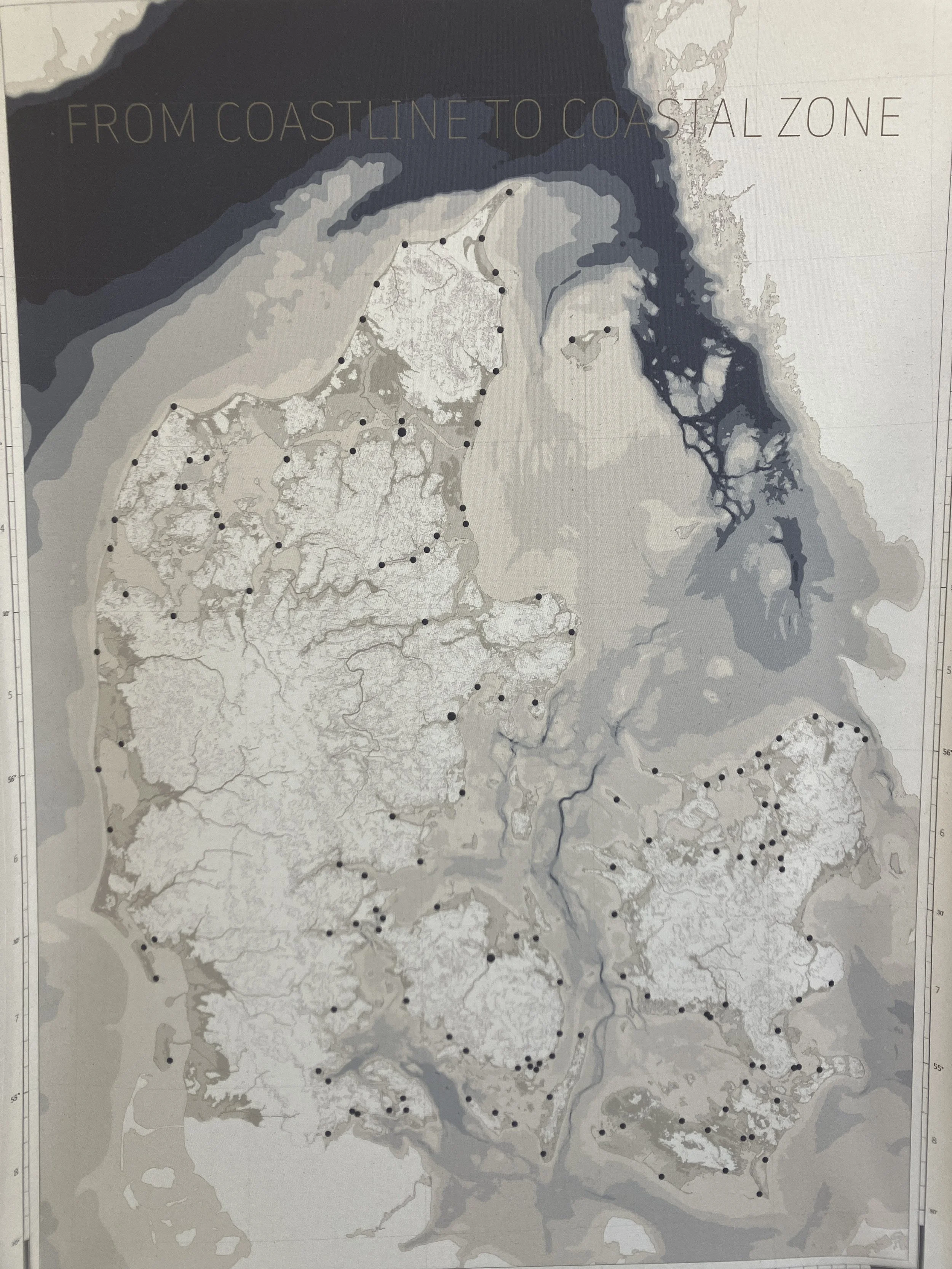

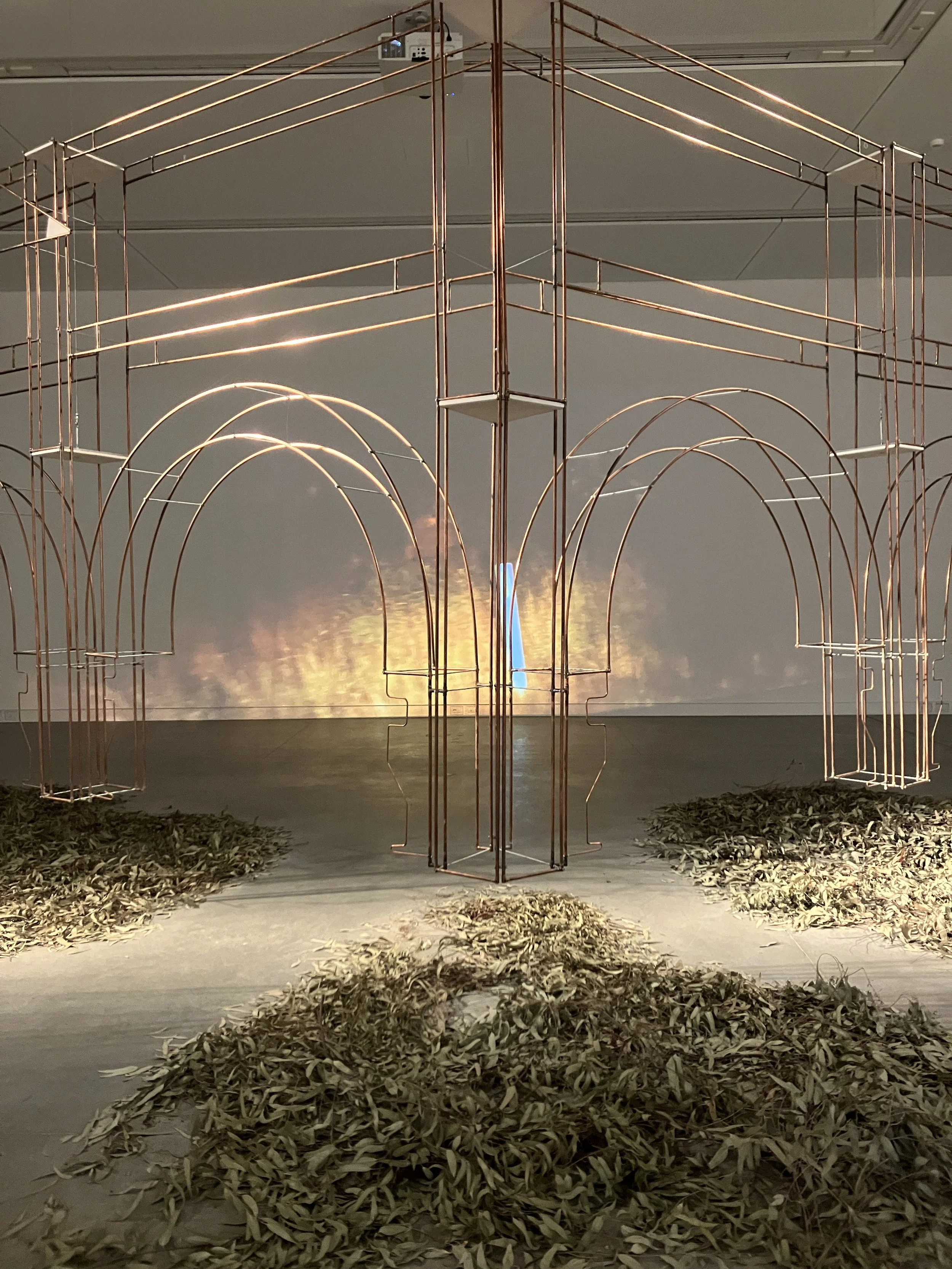

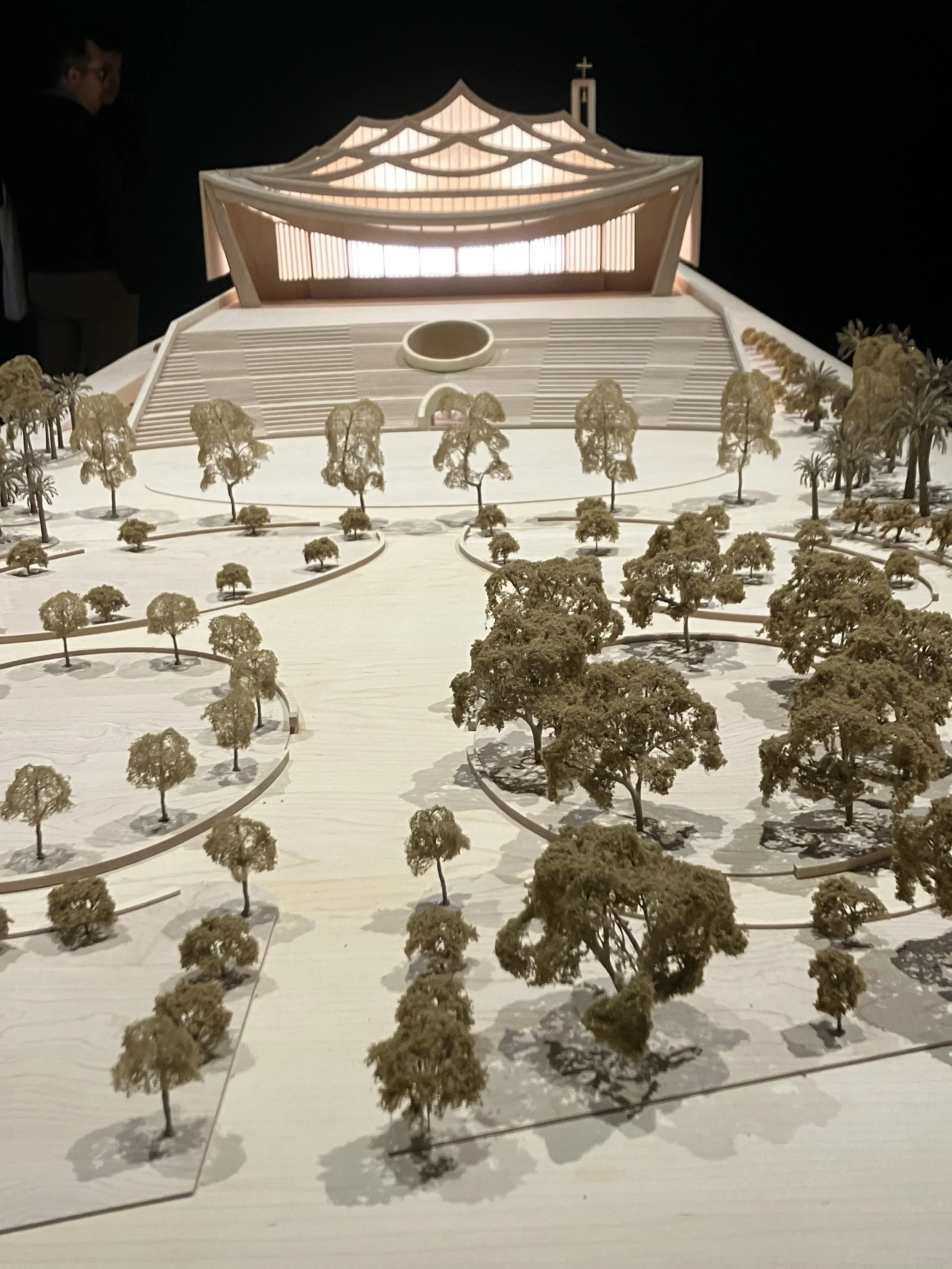

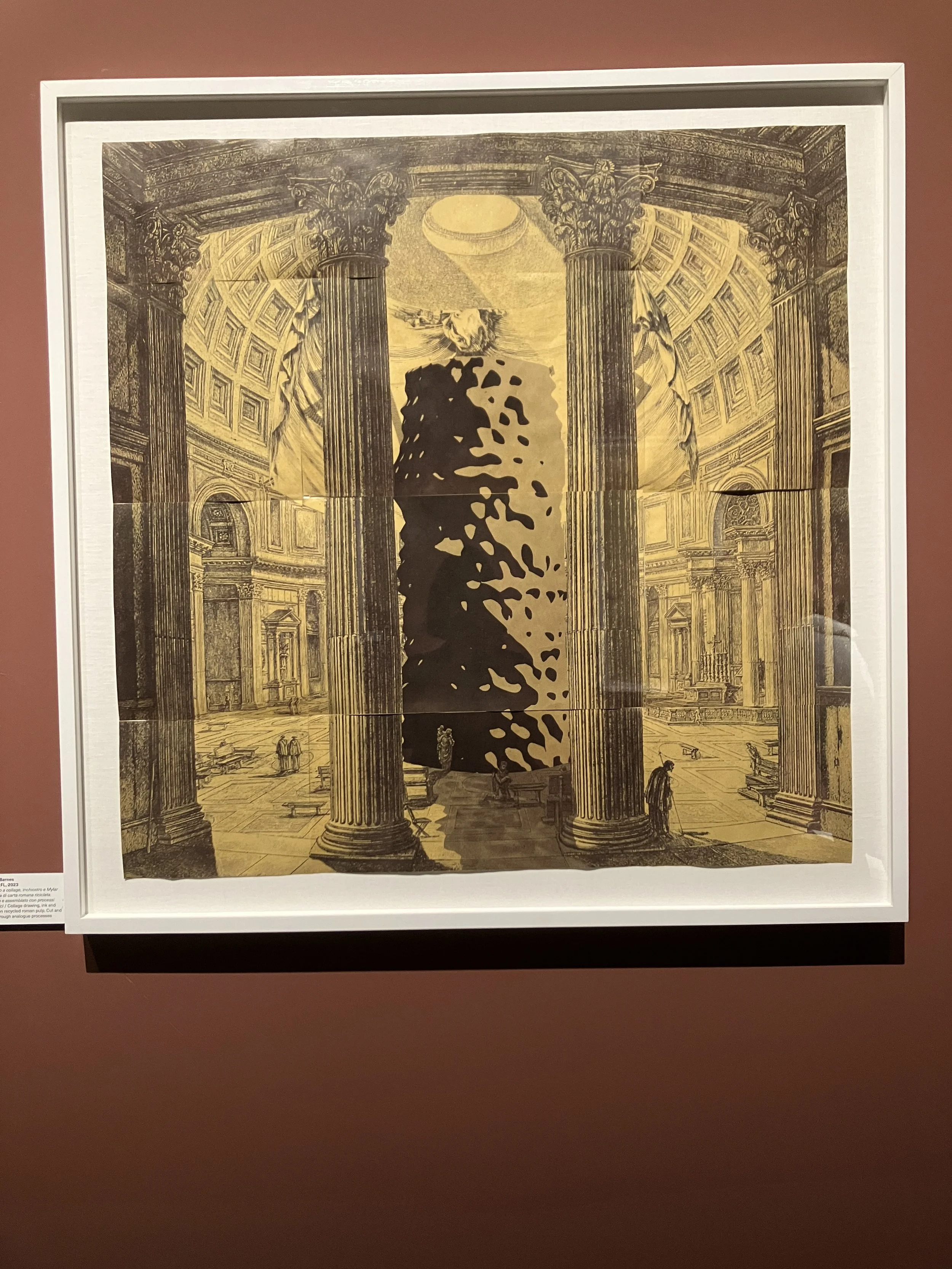

The theme for this year was ‘The Laboratory of the Future’ with curator Lesley Lokko’s introductory text laying out the approach of the exhibition, I felt, particularly clearly. She wrote about the stories missing from the ‘we’ that creates our culture, and how traditional architecture has told a single, dominant story, ignoring the experience (and spaces) of large swathes of humanity: ‘What we say publicly matters, because it is the ground on which change is built.’ Thus, there was a focus on land rights and use of space, more than designed structures, on communal experience, light and sound, object placings, material textures, and sensory knowledge.

One text particularly struck a chord for me, talking about the relationship of laboratory and workshop, how we conceive of spaces as focused on intellectual or manual work, solitary or communal labour. Lokko wrote about the balancing of head and hand as ‘at the heart of architecture, which often acts as intermediary between the conceptual and material worlds’. This re-ignited thoughts that began to germinate for me at the 2022 biennale, about starting a book on ‘the look of science’ in response to a number of pavilions where artists played with scientific aesthetics.

Many of the pavilions and exhibitions spaces also played heavily with light and shade. It was a feast for the keeper of the #MuseumofShadows, and you’ll find shadow photos interwoven with others below. There was something especially illuminating about watching little Alfie’s awed face responding to changing images, spaces and sounds, that really brought the messages of the biennale home to me, and made me think about space, identity and work. I hope it will feed into some ongoing ideas, amidst the baby brain fog.